Hillel Students Find Expression and Meaning in Art, Not Hate

A way to express what matters to them; a creative solution to real conflict. This is what students at The Hillel School of Tampa found recently in art, not hate.

For the last two months, Fine Art and Judaic Studies middle school students at the Hillel School of Tampa have been working on “social commentary” art — that which encourages its creator to interpret the world he or she lives in, not just portray it. The unit began after middle school students visited the “Art Not Hate” exhibit at the Florida Holocaust Museum this past March. They were intrigued by the theme of “creative solutions to conflict.” The students were asked to reinterpret the exhibit’s focus on the Holocaust and Post-Holocaust genocides, and apply it to their own 21st-century lives.

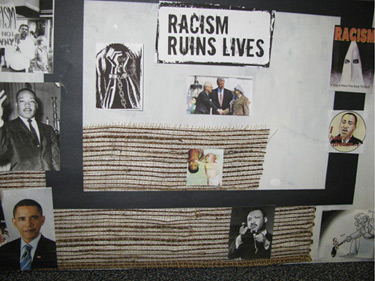

When they returned to school, students were asked to think of an issue that was important to them. This is what your art class will center around for the next two months, Hillel art teacher Debra Campbell told her students. One student, Matthew, picked fear. Shelby picked nutrition in America. Yoni picked racism. All of the students worked hard to transcend the surface of their topic, communicating the emotions that lie beneath.

Matthew’s sculpture explores the topic of fear. Fear is an obstacle blocking personal accomplishments. In order for an individual to self-actualize, he says, they have to break through the wall of fear.

“Shelby’s collage is illustrating how America has ignored nutrition and exercise and has become a country of couch potatoes. Kids especially have to be careful not to exist on fast food and junk food. She believes we are creating a society that it is susceptible to disease and ill health.”

– Debra Campbell

“Although it is portrayed here as racism against African Americans, Yoni believes that is only one example. So many races have been discriminated against that it is important to take a stand whenever people attack others because they are not of the same background or race.”

– Debra Campbell

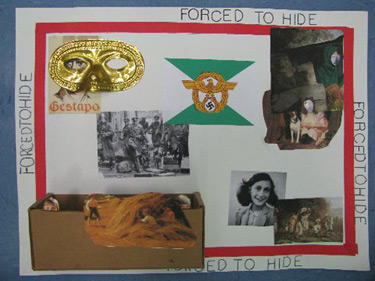

“Forced to Hide by Sydney shows how Blacks and Jews have been demeaned throughout history and forced into hiding. Her collage has a video of the Alvin Ailey Dance Company performing ‘Revelations’ that is superimposed over the art. The dancers are dancing to coded slave songs that told slaves where to hide.” – Debra Campbell

“It was really hard for them to see the difference between graphic art and (fine) art,” said Campbell, “something that will evoke an emotion rather than just tell the audience literally how to view the artwork.”

Campbell let students use whatever materials they wanted — a carry-over from the workshops that inspired the idea.

Campbell had worked with Barancik a few months beforehand at the Art Not Hate workshops at Creative Clay, a St. Petersburg organization providing equal access to art education for disabled citizens. The workshops were designed to teach problem-solving skills to middle- and high-school students by promoting understanding through artistic interaction. Campbell just so happened to be launching her social commentary unit at the time and wasn’t sure how she wanted to approach the topic.

The Art Not Hate workshops jived perfectly with what she was trying to teach, and she decided to get more involved. When she heard about the exhibit at the Florida Holocaust Museum, she knew what she wanted to do.

Using materials they selected themselves, each students’ artwork was made unique to the issue it surrounded and the emotions it expressed. One student, Nicole, made a torch-shaped sculpture she calls “Sacrifice By Fire.” An homage to lives lost in the Holocaust, Campbell says Nicole’s message is that, “If humanity is not vigilant, it can happen again.”

Nicole created this piece as an homage to lives lost in the Holocaust. The burning torch is symbolic of rememberance. If humanity does not remember the consequences of its negligence, we may experience a horror like the Holocaust again.

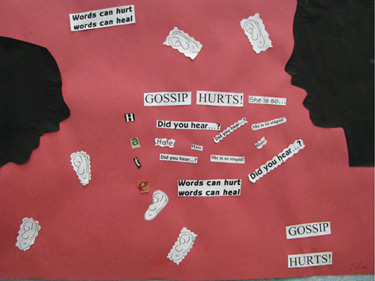

Talia's piece is a red and black stand against gossip. Words can be used like weapons to injure a person's self-esteem. We have to treat gossip like violence and be conscious non-participants.

Alex constructed a book in sections like the walls of hatred, or the black and white systems of thought that separate people.

Talia’s piece, “Words Can Hurt,” is a red and black stand against gossip. Talia chose to make a collage, which allowed her to use a lot of type in her design including phrases like “Did you hear…?” and “She is so…”

After five months of studying the Holocaust in Judaic Studies class, Amy Wasser’s students came back from the “Art Not Hate” exhibit with a focus on the concept of memory. “As Jewish citizens in contemporary America, we have no memories of the Holocaust,” Wasser says, “because we never experienced it. We know we need to remember what happened, lest we let it happen again, but how can we remember something we never experienced?”

Like Campbell, Wassser asked her students to use art as a medium to express their feelings. Each student chose a different topic of memory and created an original piece of art. One student constructed a wooden table, painted with names of victims and splatters of bright red paint. Tiny figurines scatter across the length of the table toward a rainbow pattern, symbolizing freedom. Another student constructed a tree-like sculpture, tall as an eight-year-old, and hung a poem on the wall beside it. Another made a concrete wall with swastikas on it, reminiscent of the walls of the ghettos that kept his ancestors inside.

Amy Wasser's class chose memory as the topic of their social commentary unit. This student crafted a long table, symbolic of Holocaust victims' long trek toward freedom and humanity's journey toward peace.

This student of Amy Wasser's constructed a tall tree with real wooden branches and placed a poem on the wall beside it. Many of Wasser's students incorporated text into their work.

This Judaic Studies student constructed a ghetto wall out of salvaged wood and desecrated it with swastikas like the ghetto walls that kept his ancestors prisoners.

When they finished their projects, students wanted to test their pieces out in the Rembrandt in Hightops Youth Art Competition, held annually at the Old Hyde Park Gallery in Tampa. They wanted to see if anyone would “get it,” says Campbell — if they had done a good enough job getting below the surface of their topics and still having people viewing it as a work of art.

They had. Out of 15 awards, five of them were given to Hillel students (four of the awards for their social commentary art).

Campbell says she will definitely teach the social commentary unit again in her class, because “using the theme of ‘creative responses to conflict’ enabled the kids to talk about things that were important to them and present them in their own, independent style.

“Rather than teaching techniques and materials,” she says, “this was one time that the kids were able to take everything they learned and turn it into a very personal work of art.”

The fabric of this piece suggests lives weaving together, flexible ways of thinking, or the multi-colored flags of a planet sewn together. Wasser's students chose mediums appropriate to their topics of choice.

These ghostlike figures are lost against a black background, separated by barbed wire and captioned by bright red letters, spelling out their ultimate fate, as if to say, “This is the fear we need to remember.”